By Louise Nayer

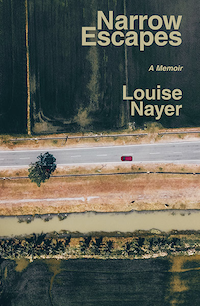

Nayer is the author of six books, including Narrow Escapes: A Memoir, out in March. She is teaching a memoir writing course with us this spring.

The Genesis of a Memoir

Visions of camels trekking across the beach I camped at when I was 20 years old and the Sirocco wind that almost knocked me off my feet filling my eyes and mouth with warm sand as I stood at the edge of the water. Hitchhiking from Beni Melal to Marrakesh in extreme heat and getting picked up by a couple from Wisconsin in an airconditioned car. We stopped to visit a rug factory where six-year-old children worked the looms. I learned later that many of them went blind. My memories gripped me, held me, and said, “Write about me!” Write about leaving New York City and my parents for California, alone with a huge round mirror in the back where a dear friend wrote, “Trust yourself” in red lipstick. My mother, who rarely cried, dressed in an ultra-suede suit she made herself, cried as my car pulled out of Greenwich Village for San Francisco. About the accident that burned my parents and the wells of grief I needed to cry out. Landscapes of leafy trees in Michigan and the flat lands of the mid-West and majestic mountains of Colorado. What did it all mean?

Some memories just stay there, lying in wait, nudging you to write about them until you finally say, “Okay. Stop bugging me. I’ll write about you.” And what was this memoir really about? Maybe I needed to go far away to let go of my grief ? And why did I do these risky acts? Was it the times? The late 1960’s and early 1970’s?

I submitted a piece about Morocco (twice) to a publication that rejected me twice. “Not enough of an arc.” What did that mean exactly? Then, “This could be a book.” After writing and publishing one memoir over many years, Burned: A Memoir, about an accident that burned my parents, I turned to fiction and had the draft of a novel. I didn’t really want to write about myself again. But I took a detour, as often happens in life. This book took over and now, many years later, Narrow Escapes, will be published in mid-March.

Finding the Arc

The “aha” moment of what a book is really about can often come after many pages are written. I thought for a long time that my book was about finding love. I seemed to run away from love. Perhaps the fear that it could all blow up? Even though that is a theme, I realized that what I really needed to do was break away from my accomplished parents and their expectations. I wanted to be a poet. It was a hard route to take, a route of the heart. I would waitress, do “Kelly Girl” jobs and write and write and write. Writing was a passion. So the book was about finding my path, shushing the voices of “should” and embracing the real me. Sometimes writers can spend hours and hours and days and days on where to start the book, and where to end the book. Even if it’s all plotted out as some do, it’s important to be open to change. The story is not fixed until it is published, if that is even your goal. Here is the link to piece I wrote on narrative arc.

Sensory Detail

“Show don’t tell,” “Use all the senses.” I often teach students to focus on a sense they don’t often use like smell and touch. How the fabric of the chair feels against your body. The particular smell in a bakery reminding you of the scrumptious chocolate eclairs you devoured as a child. Or the acid taste in your mouth of coffee as you race to BART. During the multiple revisions over a number of years, I made verbs more active, made sure to show the landscape or the room, added smells and taste and even with all the additions I’m sure so much was left out. But creating a vivid scene which the reader can enter, like sinking into a soft sofa, is what makes the writing shine. Close your eyes and listen to the sounds of the fluorescent lights or the traffic or children playing games. Smell the cooking smells and touch your hands together. Are they hot or cold? Put all this into your writing. This also helps with describing character. Here is a link to a piece I wrote on character.

Dialogue

As a poet for many years, I had no idea how to write believable dialogue. A lot of my characters sounded the same. In Burned: A Memoir I had the child’s voice and then the voices of the adults. I’m not sure it was always accurate—but at least those voices were different. Also, my dad was Jewish, a true intellectual and quite emotional. My mother was Christian, practical and rarely showed intense emotion. That made it easier as they were so different. I learned to shorten dialogue, to do away with tag lines (he said, she said, when I they weren’t necessary). Go to coffee shops—sit on BART and listen to people speak (if they’re not just connected to their phones). Go to the airport and listen to people greeting and saying goodbye to each other. Listen to the rhythm of speech and how it is different depending on where you are from. Here is a link to a piece I wrote on dialogue.

Also, when you use dialogue, you are creating a “scene” and not just summarizing material which can get tedious.

Putting Your Story Out into the World (or to give to your family or friends)

We often have secrets, regrets, ways we see life differently that we would like to write about. Language is our canvas, the taste and sound of words. Something gnaws at us—a missed connection with a lover, something we wanted to say to our parents but never got to say. Sometimes the moments we write about are moments of pure joy. In Narrow Escapes, I’m driving alone in a car with no air conditioning or radio, fragments of poems spinning through my mind. For a few days I am completely liberated from the voices telling me I should have a boyfriend, a great job, a perfect place to live.

From Narrow Escapes …”The time inside my Camaro was all my time. Crazy images spun through my brain, trees like dancers, the blue sky a silken robe, the cars in front of me huge beetles, the road an alleyway to the heart, my heart not broken on this stretch of road; maybe my heart had never really been broken when my parents disappeared. I wanted to believe that. I was always trying to get to an unbroken heart.”

Whether you write and never show anyone—or write to pass down memories to the next generation—or want to be published, the impulse is the same. We are all story tellers by nature and many of our stories will never get told. Memoir writing is a way to tell your story, to pluck what is most important from your life—lessons learned, beauty witnessed, sadness endured to leave something to the world.