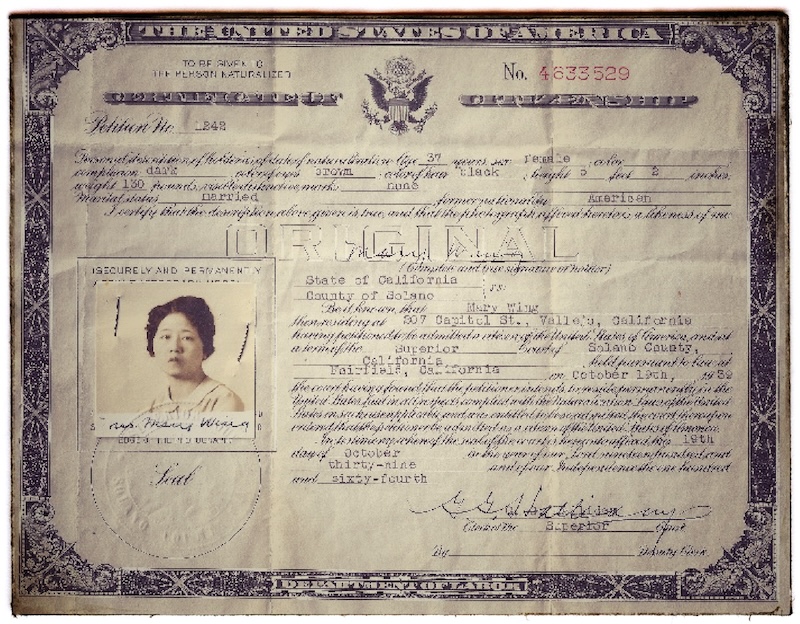

My grandmother Mary was born in San Francisco in 1902. Both of her parents were American-born as well — her father in San Francisco and her mother in Monterey. In 1854, her grandfather had immigrated from China to San Francisco at the tender age of 12; her grandmother came in 1874. Our family’s long history in the United States has always been a matter of intergenerational pride. My grandmother by herself had experienced and contributed to nearly a century of American life when she passed away at the grand age of 96. So I was puzzled when I discovered a certificate of naturalized American citizenship among my grandmother’s papers. Naturalized citizenship is granted by the United States to immigrants who meet specified qualifications. My grandmother was a second-generation native-born American. Her naturalized citizenship certificate represented a mystery to me – especially because I knew that for Chinese Americans, birthright citizenship was a hard-won right, one that would not be voluntarily surrendered. I unraveled the conundrum by diving down the rabbit holes of history.

In 1868, Congress passed the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Its first sentence stated:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

The 13th Amendment freed enslaved people. The 14th Amendment conferred citizenship upon them. What is more, its wording ostensibly proclaimed that all people born in the United States were guaranteed citizenship. Yet 30 years elapsed before American-born Chinese were granted this constitutional right.

In 1895, Wong Kim Ark, a native-born San Franciscan, returned from a trip to China only to find himself denied entry to his birthplace. The U.S. claimed he was not an American citizen on the basis of his parents not being American citizens. Wong’s parents, immigrants from China who had resided in the U.S. for more than 15 years, were prohibited from becoming naturalized citizens by the Chinese Exclusion Act. The U.S. further maintained that being Chinese and a laborer by occupation, Wong was himself subject to the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred Chinese laborers from the country.

Wong argued that he was a native-born citizen by virtue of the 14th Amendment. He had lived his entire life in the U.S. and had never renounced loyalty to the U.S. In 1898, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 6 to 2 in his favor, holding that the 14th Amendment guaranteed citizenship to all those born on U.S. soil, regardless of their parents’ race or nationality.

It was because of Wong Kim Ark’s victory that my grandmother Mary was a birthright American citizen. Yet in 1920, the U.S. stripped her of this right.

In that year, Mary married my grandfather, Fung Gum Wing, a Chinese immigrant. The Expatriation Act required her to assume her husband’s nationality. For Mary, this was a Catch-22 of gender and race. First, the law reflected the doctrine of couverture: a married woman had no legal existence apart from her husband, no rights or obligations separate from his. Second, the Chinese Exclusion Act’s long reach not only barred Wong Kim Ark’s parents from naturalization in the 19th century but also made it impossible for Mary’s husband to become naturalized in the 20th century. The law, enacted in 1882, was the first federal law to explicitly ban immigration and naturalization on the basis of race. It was not overturned until 1943.

Mary spent nearly 20 years without any constitutional rights or protections. During this time, she gave birth to one son – my father – and four daughters, all in Oakland. A cloud hung over the happiness of Mary’s motherhood: might her children’s birthright citizenship also be imperiled?

In the 1930s, amendments to the Cable Act permitted my grandmother Mary to become an American citizen again – if she applied for naturalization. One of the most vivid memories of her youngest daughter Loretta was observing her mother studying long and hard to pass the citizenship test.

My grandmother Mary was awarded a certificate of naturalized citizenship in 1939. It is ironic to say the least that the certificate identifies her former “nationality” as “American.” In 2014, the U.S. Senate apologized to Mary (posthumously) and to all women who lost their birthright citizenship because of who they married.

Linda Wing, Ph.D. is an OLLI @Berkeley member and volunteer who spent more than 45 years working to transform public schools in order to enable students in the nation’s cities to learn and achieve at high levels.